“He was an artist to his finger tips, no doubt about that…” A Tour of Weeks Hall’s Studio

In the 1940s, William Weeks Hall had an art studio in the southeast front room on the ground floor of the Shadows looking out over his formal garden.

A brightly painted cabinet housed Weeks Hall’s art supplies, including paints, brushes, smaller canvases, and probably a “thousand sheets” of bread wrapping paper that he used for sketching, especially when teaching. The cabinet is painted in a Norwegian folk art style, which according to Clement Knatt, long-time employee of Weeks Hall, was done by the artist.

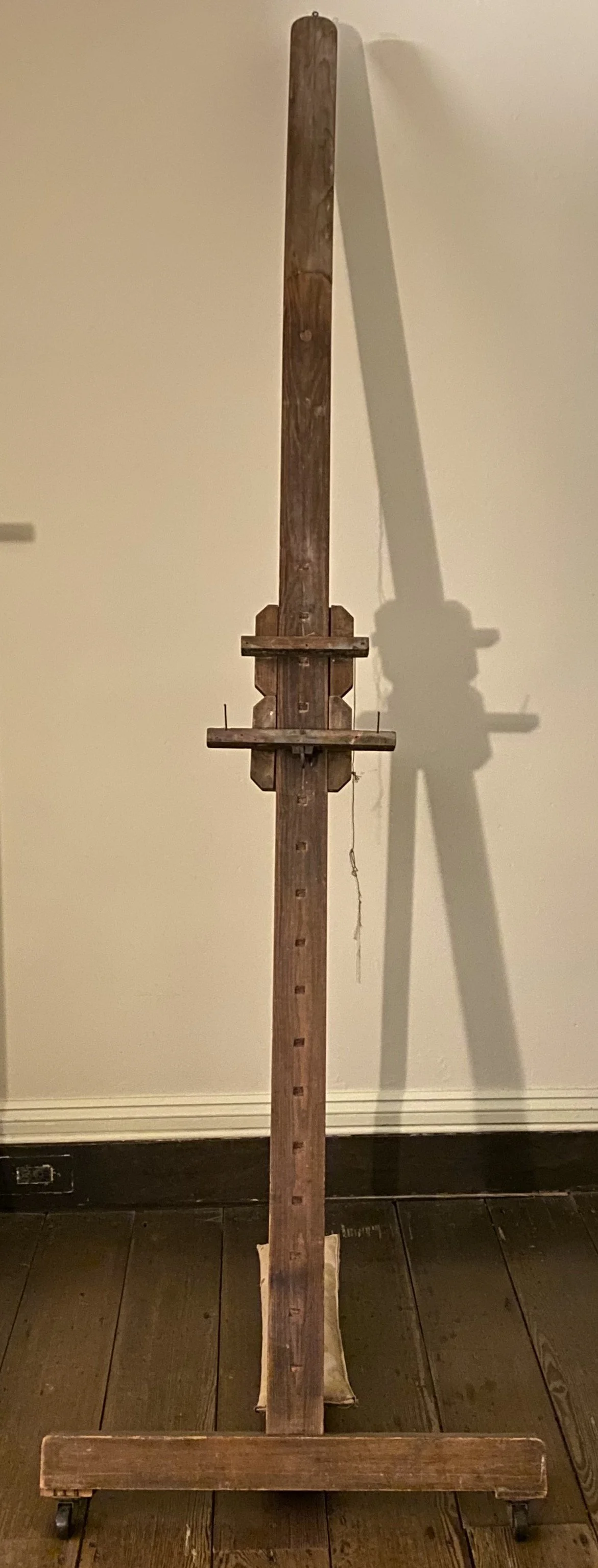

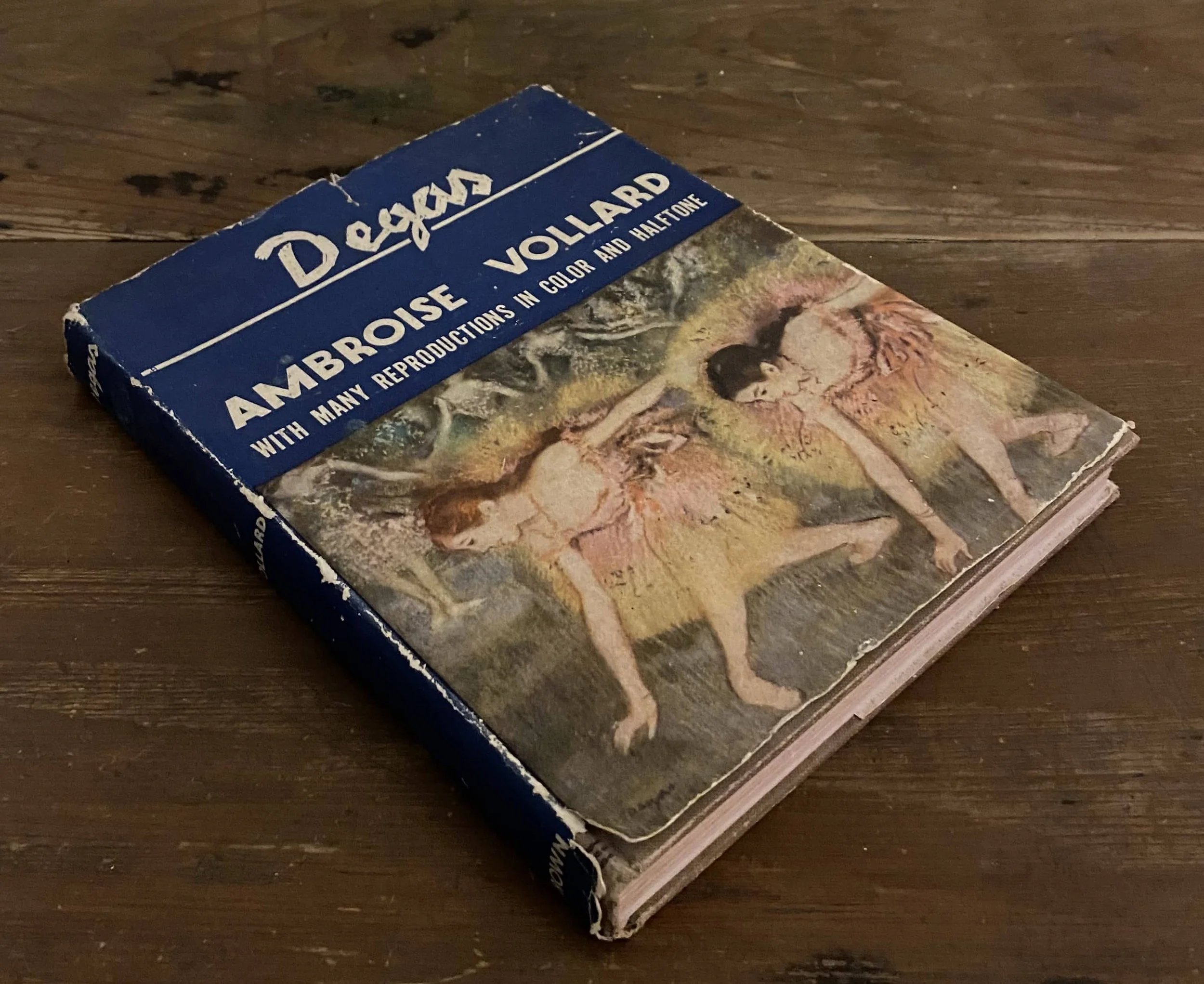

A very tall wooden easel was probably used by Weeks Hall as a student at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia from 1913-1918. At the Academy, he was the envy of the other students because of his fine personal art library. Weeks Hall often said he learned more about art by looking at the illustrations in these books and by going to exhibitions to see the work firsthand than he ever learned from his teachers. This may account for his own teaching methods when students attended classes at the Shadows or when he taught at Tulane in the 1940s. “The only way that painting can be ‘taught’ is to instill enthusiasm. If you can impart knowledge also, all the better, but it is useless to hand over an unlit torch. All the great teachers have had this quality, not many have had great knowledge.” [Hall, 1939]

Throughout the 1920s-1940s, Weeks Hall exhibited art at shows both in New Orleans and in a 1945 exhibit at the Academy. His New Orleans friend Gideon Stanton acted as an agent selling his paintings, though it is not known how often sales were made, nor how many exhibits his work might have been shown in or where. We do know Weeks Hall’s 1923 landscape of the Shadows as he believed it had looked in his great-grandparent’s day won first prize in a 1926 juried exhibit where he was complimented for capturing “the grandeur of those oaks with their trailing moss.” [Alma Thorpe to Weeks Hall]

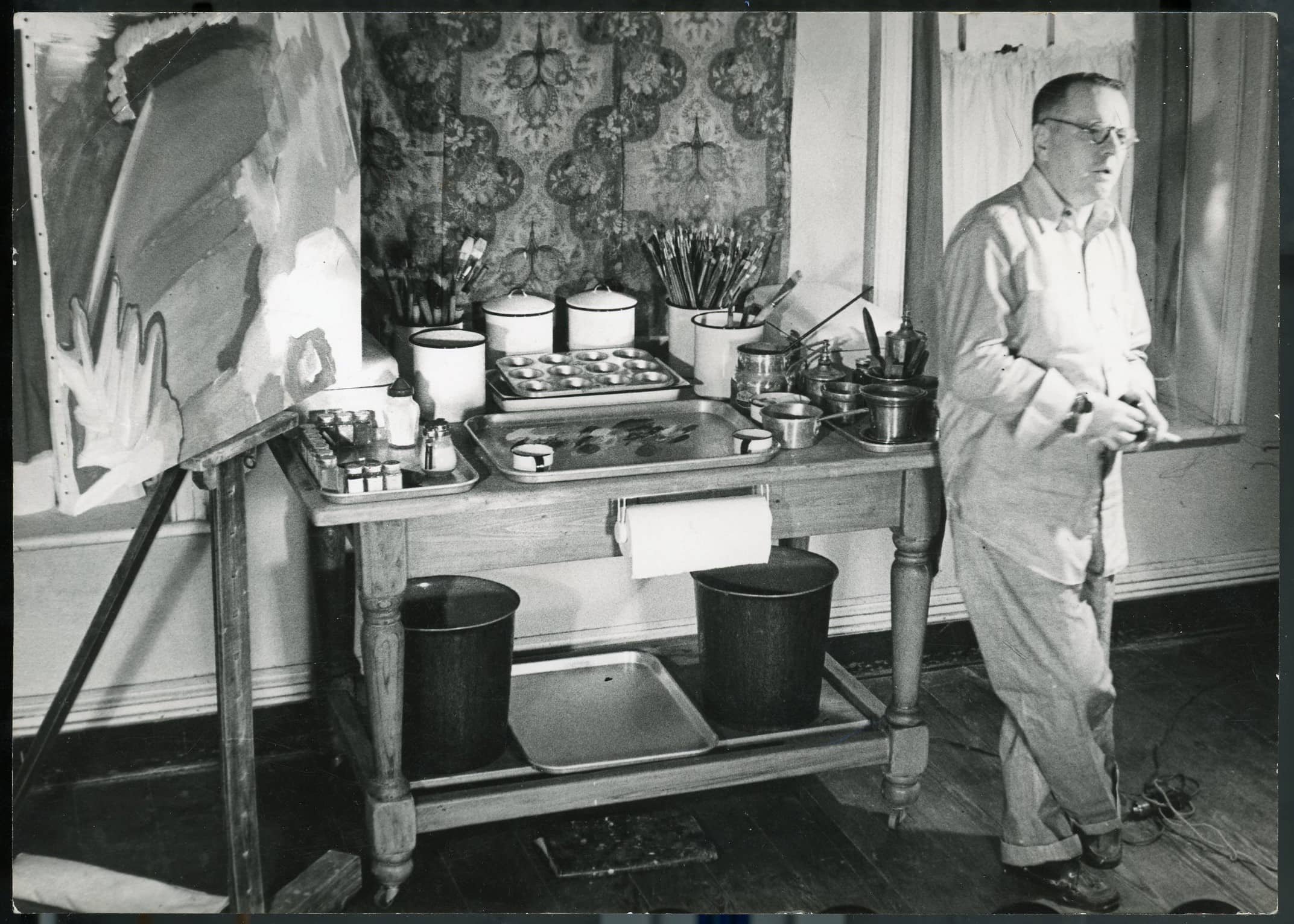

Weeks Hall in his studio. From the collection of the Shadows-on-the-Teche.

The table full of art supplies was commissioned by Weeks Hall for his studio and made locally. The enamelware boxes, cannisters, trays, bottles of paint, brushes, and art box with palette all belonged to and were used by Weeks Hall.

A large footed ceramic bowl of fruit is just one of the family heirlooms Weeks Hall confiscated to fill with onions, bell peppers, lemons, flowers, Mardi Gras beads, and even watermelons, which he then painted.

Weeks Hall painted landscapes like the Shadows, still lifes, portraits, nudes, flowers, and then some less traditional work such as a very colorful one of bathers amidst oaks and spider lilies done for Stanton, a large painting of an African dance mask and WWI gas mask titled “Two War Masks,” and the impressionistic view of two Marid Gras “Maskers in Sunlight.”

In the early 1930s Weeks Hall became interested in Eastman Kodak’s new Kodachrome film and experimented with this new product composing slides which were similar in design and feeling to his paintings, landscapes, portraits, still lifes, and imaginative assemblages of onions, squash, limes, and pearls.

As the restoration of his family home began to absorb his time and attention more completely every year, he gave less of himself to his art. His friend Anna Ingersoll, a classmate at the Academy and an admirer of his work, remarked on this. “Many of us felt quite bitterly about the Shadows when it absorbed him after his return from Europe and he painted less and less. But when he showed it to me—I think in the Spring of ’29—I understood the hold this beauty had on him.”

Though he occasionally taught art at Tulane University in New Orleans and held classes in his New Iberia studio and at other locations in town, Weeks Hall himself “painted less and less,” and with more and more frustration. In 1939 he wrote: “My own painting is weighted down with tiresome, bald statements repeated witlessly. No imagination…. I can never remember to imply and suggest. I must always use a sledge-hammer.”

Weeks Hall was his own worst critic. He sometimes hid behind his “smashed arm” using it as an excuse for not painting, but at the same time he always knew that was not the problem. His mind was occupied elsewhere. “Perhaps my mind is too slick and too brittle. Not disciplined enough. And I know I won’t improve it by my mania for research. That’s just a pretext to forestall the day when I must really begin to paint. I know all that—but what are you going to do? Here I am living alone in a big house, a place which overwhelms me. The house is too much for me. I want to live in one room somewhere, without all these cares and responsibilities which I seem to have assumed from my forbears.”

Henry Miller, who might be considered a more objective critic, thought that Weeks Hall was a great artist, and that we need only look through the windows beyond the easels and canvases of the studio to a larger “canvas.”

After a visit in 1941, Miller wrote that Weeks Hall had not only assumed the responsibilities from his ancestors to preserve the family home, but that he had made the Shadows a “distinctive” work of art. According to Miller, Weeks Hall was “living and breathing in his own masterpiece, not knowing it, not realizing the extent and sufficiency of it…. He was an artist to his fingertips, not doubt about that…” [The Air-Conditioned Nightmare]

Originally published in The Weeks Hall Centennial Year pamphlet. The Centennial Year celebration of Weeks Hall’s life ran from October 1993 to October 1994.