The Civil War in Sugar Country, Part III: "The Closing of the War...Leaves Us...Exhausted & Ruined", 1864-1865

Originally published in Harper’s Weekly on August 11, 1866, this illustration shows people in downtown New Iberia. Library of Congress 2010651247.

As 1863 ended and the new year began, there was no cause for celebration in the Weeks family. 1863 had been the year that the war arrived in Teche Country, knocked on their door and moved in, an unwelcome visitor. In addition to the devastation brought about by armies on the move, 1863 also brought great devastation to the family with the personal tragedies of the deaths of Allie Weeks Meade’s son, Everard Meade, in Texas, his cousin David Weeks Magill in Vicksburg, and then Mary Weeks Moore’s death at the end of the year.

With these deaths, all hope was lost that life would ever again go back to “normal,” to what it had been before 1861. Mary’s son William Frederick Weeks rationalized, “God was merciful to remove her from scenes of destruction & wretchedness by which she was surrounded, nothing about her premises was sacred to the polluting touch of the barbarians. Even the garden & tender plants she used to love & cherish was destroyed by being converted into a mule lot…”

But life goes on, even amidst war and death. The January mail carried not only the news of Mary’s death, but also the birth of William and Mary Palfrey Weeks’ new daughter, Harriet, born at the Shadows on January 15, 1864.

Even in mourning, family members gathered in DeSoto Parish to plan a March wedding for Allie and Thomas Weightman. As Charley Conrad Weeks’ wife, Maggie, wrote, “[Allie], poor thing, has suffered so severely [due to the death of her only child and the death of her mother], her engagement does a great deal toward cheering her…” Indeed, births and a wedding did “a great deal toward cheering” everyone as they struggled to make a life for themselves and their families under unusual and difficult circumstances.

William made it home in early 1864 to see his new daughter and check out the various family landholdings, including Grand Cote and the Magill plantation near St. Martinville. He found everything as well as could be expected given the plantations were practically deserted. There were corn crops on both places, but no mention of a sugar crop.

It was during the Civil War that William expanded upon his role as manager and provider for the family. It is to William that Alfred, Charley, Allie, and their families went for advice and assistance.

After fleeing Louisiana in advance of the Union Army and before returning home permanently, both William and Charley used their teams, wagons, and drivers to haul various supplies for the Confederate Army. William used his wagons and enslaved laborers to haul ties for the railroad. Charley converted his cane carts into wagons to haul clothing made in the penitentiary at Huntsville to Shreveport for the Confederacy.

The newlyweds, Allie and Thomas Weightman, lived “in a log cabin with brush shades on three sides” at the edge of the prairie in eastern Texas. They grew cotton, and Allie was spinning and weaving cloth for use by the army.

William felt they should all try “to make a crop of cotton, otherwise we will be all bankrupt.” Even when his crop was attacked by worms, he had hopes to get more “than we can employ for our spinning purposes, which, by the by, takes a great deal. I have two looms going here [near Houston?] & one in Walker County. Up to this time we have made some 1200 yards of excellent cloth.”

William also began to diversify, a pattern he was to continue after the war. In addition to cotton, he was growing corn, and “…[as] our corn is a long distance from market, I propose to buy a large number of hogs to fatten this fall & put up a large quantity of fat port & bacon…” He also raised beef cattle. There was a good market for foodstuffs in war ravaged Louisiana.

By November 1864, Allie and Charley moved to Walker County to be near brother William. William kept very busy not only managing his own properties, but also trying to secure places for Allie and Charley to live and ways in which they could support their enslaved people. It was William who rented property on Brazos River for Allie and on the San Jacinto River for Charley and his family.

William used his experience and skills well. As his sister-in-law Maggie observed, “Bud is certainly one of the greatest managers I ever saw. He has everything in great abundance around him, & his store rooms from which we get our supplies are well filled.”

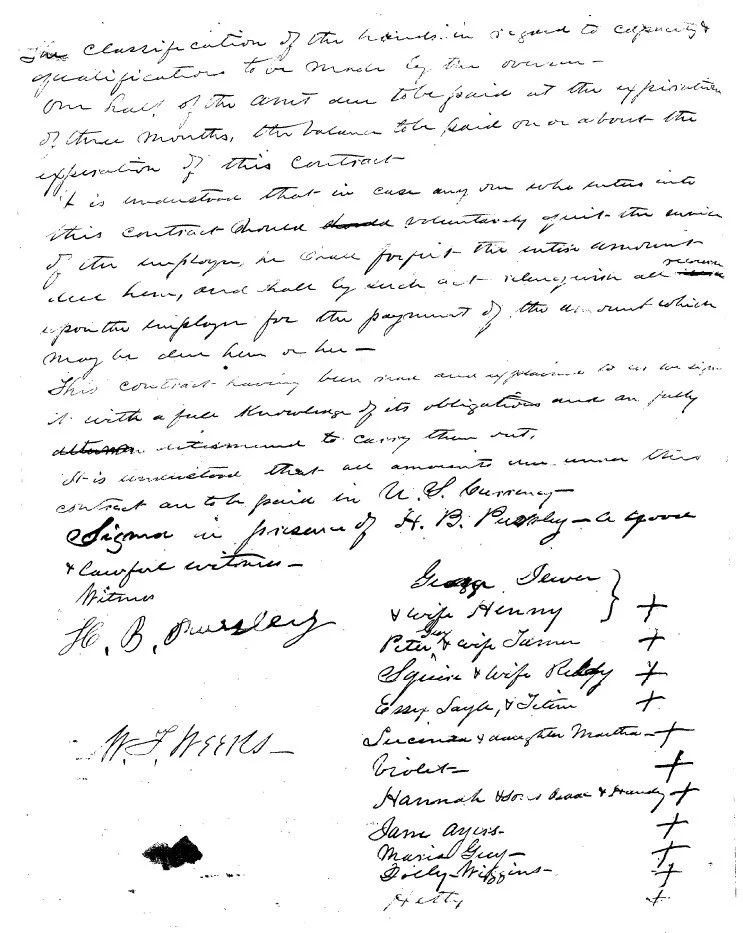

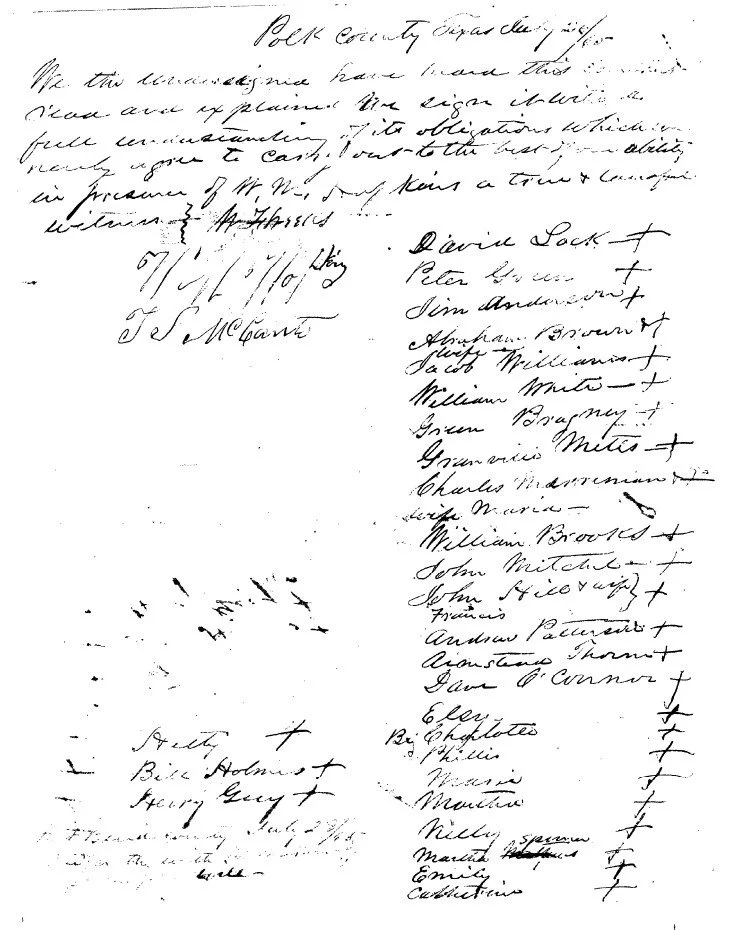

With the death of his brother Alfred in late December 1864, and the surrender at Appomattox in April 1865, William yearned to return home. He tried to establish a contract with his formerly enslaved laborers so they could return to Louisiana and rebuild the plantation. But despite his wishes, he was forced to remain in Texas as so many people depended on him. “My whole life has been spent taking care of property of other people,” he wrote John Moore in January 1865. He remained in Texas for most of 1866, harvesting crops, selling properties, and finalizing work agreements with freedmen.

Allie and her husband, as well as Charley and his family, returned to the Teche Country in 1865. Though Charley was forced to “driving beeves” and selling firewood to support his family, his wife, Maggie, believed “It is very pleasant to be at home, to think we do not have to be wanderers and exiles anymore…”

But it was readily apparent to everyone there were years of hard work ahead if they were ever to achieve some of the pre-war success and lifestyle. A nephew of John noted “The closing of the war, this section of the country having been subjected to the ravages of both armies for the last two years, leaves us all in a very exhausted & ruined condition.”

Labor agreement signed in Walker County, Texas on July 25, 1865 between William Frederick Weeks and newly freed men and women. From the collection of the David Weeks and Family Papers.

While both William and his wife, Mary, expected “hard times,” they both seemed ready and willing to do what needed to be done to ensure the future for their children. “Planting will not succeed for several years yet. You must commence on a very small scale, & with cotton at first.”

There would be many changes—changes in labor and relations between planter and labor force and changes in crops until labor needs were met, sugar mills were repaired, and the market system was again in place. The 1860-1861 sugar crop, the largest to that date, consisted of 459,410 hogsheads of sugar, valued at $25,000,000. The 1864-1865 crop dropped to 18,000 hogsheads valued at about $2,000,000.

But there was no time “to cry over spilt milk.” The war was over. The first step had to be taken. As Mary Palfrey Weeks told her husband, “You must commence.”

Originally published in the Shadows Service League newsletter (Vol. 17, No. 8), August 1995.