“Do send me something to read”; Mary Weeks Moore on Reading

“I have nothing to read and the weather is so gloomy that it gives me the horribles.”

So wrote the young mother Mary Conrad Weeks to her brother Alfred Conrad in 1822. At the time, she was living at Parc Perdue plantation. Her husband of 3 1/2 years was absent from home frequently, and she only had her two-year-old daughter to keep her company. Her letters indicate she was alone much of the time and that she felt isolated from her family. She and Alfred corresponded regularly, and Mary almost always requested he try to send her books, sometimes naming specific titles and at other times just asking for books in general. Mary instructed her brother, who was a storekeeper at “Attackapas Church,” [St. Martinville], to try some of their “novel reading friends” to see if they had books they might lend her. It seems she borrowed items from friends and family on a regular basis, just as she swapped plants and seeds.

One of those friends, Maximilian Brashear, searched his house in vain upon receiving Mary’s request for reading material. “I am extremely sorry to tell you that I have not a Novel to send you that you have not read—for I would not have you get hysterical for the world—as I don’t think it suits your disposition at all.” [July 7, 1822]

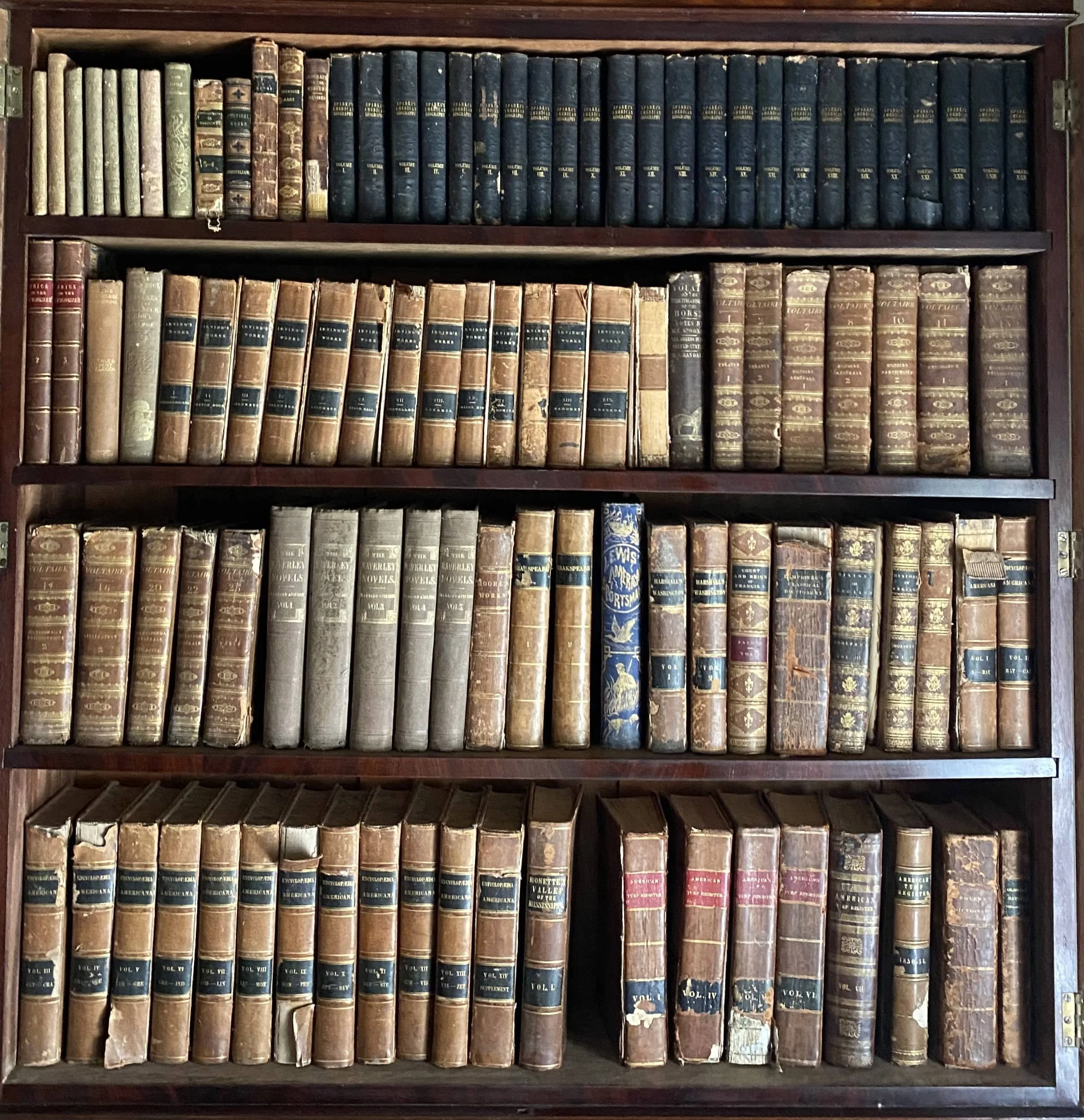

A selection of books from Mary’s personal library that are display in the Shadows.

As witnessed from her correspondence, Mary was an avid reader throughout her life. She read novels, newspaper accounts of political happenings, “how-to” books on gardening, and popular periodicals like Godey’s Lady’s Book. She was not alone in this leisure-time activity. Nineteenth-century America saw a tremendous increase in the public’s interest in novel reading. Fiction, at first, was not considered respectable reading material, but publishers promoted early fictional works for their value in teaching moral lessons. An 1839 publication, Etiquette for Ladies, recommended certain authors whose works might encourage “cultivation of the intellectual powers, so necessary to the fulfillment of the female mind.” The list included Jane Austen, James Fennimore Cooper, Charles Dickens, Maria Edgeworth, Washington Irving, and Sir Walter Scott.

In a letter written to husband, John Moore, in 1853, Mary wrote “I wish you would not forget Uncle Tom’s Cabin. I have seen so much of it in the papers.” Uncle Tom’s Cabin, written by Harriet Beecher Stowe, was the best-selling novel in America before the Civil War. Published in 1852, the two-volume anti-slavery novel sold 20,000 copies within three weeks of its publication. By mid-1853, 1.2 million copies of Uncle Tom’s Cabin had been sold. Newspapers in the South condemned the book and appealed to their readers not to encourage Stowe by purchasing her novel. The New Orleans Crescent accused Stowe of forgetting “all the sweet and social instincts of her sex” by her inflammatory novel which surely would lead to a slave insurrection. The New Orleans Picayune said Stowe was “deficient in delicacy and purity of a woman.” No wonder Mary wanted to read the book!

Other novels mentioned in Mary’s letters were Goldsmith’s The Vicar of Wakefield, first published in 1766, and Belinda Portman, probably the romantic novel by the Irish novelist Maria Edgeworth written in 1801. Maria Edgeworth (1767–1849) wrote many novels that retained their popularity throughout the 19th century. Ladies were encouraged to read Edgeworth’s novels as a means of developing their “intellectual powers.” The Shadows’ collection includes a set of twenty novels by Edgeworth that are bound in ten volumes and were published in New York by Harper & Brothers in 1856. These belonged to either Mary or her daughter-in-law Mary Palfrey Weeks. Volume 1 contains an especially interesting “Essay on the Noble Science of Self-Justification” which explains that “a lady can do no wrong,” though she may have to do battle with those who might question this fact, namely husbands! The essay, first written in 1787 and still read in the 1850s, instructed women on how to deal properly with any criticism of themselves.

In addition to novels, Mary often requested that John send her newspapers from Washington, D.C. Alexis de Tocqueville, a Frenchman who visited the United States in the 1830s, observed “Americans were addicted to reading newspapers.” Mary’s favorite seems to have been the Herald of the Union, though she also read the New Herald (her son William’s subscription), and the Picayune, among others.

At times, John did not respond to his wife’s requests quickly enough to suit her. In 1852, Mary, at home in New Iberia while John was serving as Louisiana’s congressman in D.C., wrote chiding him, “Do send me something to read. Your predecessor was always sending some entertaining work to his wife, and there are good bookstores in Washington. They are very cheap. You know how very isolated I am, how very fond of reading.” An 1853 letter from Mary to John states, “I have read everything about the house. I wish there was a good Library in this place, in dark bad weather when I cannot go in the Garden, time hangs heavy on my hands.”

Reading and gardening were Mary’s two favorite pastimes. In 1859, she requested John “not forget Bridgeman’s work on vegetables, and another on the culture of flowers.” He apparently filled these requests as the Shadows’ collection holds a copy of Thomas Bridgeman’s The Florist’s Guide, published in New York in 1847. This popular “how-to” gardening book contains “Practical Directions for the Cultivation of Annual, Biennial, and Perennial Flowering Plants of Different Classes, Herbaceous and Shrubby, Bulbous, Fibrous and Tuberous Rooted, Including the Double Dahlia.” The author described himself as a “Gardener, Seedsman and Florist,” and published the book himself.

Whether they were romantic novels by Sir Walter Scott or Maria Edgeworth, newspapers reporting events in Washington or New Orleans, Godey’s Lady’s Book describing the latest fashions, or gardening books prescribing the best time to plant dahlias, Mary read them all, even unto death. As her son Alfred described, on December 28, 1863, Mary “sat up until one o’clock at night talking to Mrs. Conrad and my wife. Seemed very cheerful, laughed at the Yankees, & went to bed with a candle & a new book someone had sent her.” They found her the next morning “with her head on one hand & her book in the other, without any sign of any struggle, the picture of peace & quiet.”

Originally published in the Shadows Service League Newsletter (Vol. 13, No. 7), July 1991.